Howard Payne University mourns the loss of Dr. Gary Price, 1960 HPU graduate, who passed away Monday, August 10, 2015. Please keep his family in your thoughts and prayers during this difficult time.

The following story was originally published in the summer 2011 issue of the Link, the magazine of Howard Payne University.

Price for Student Aid

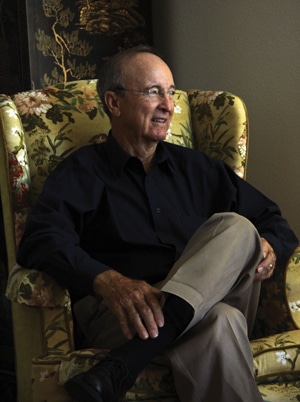

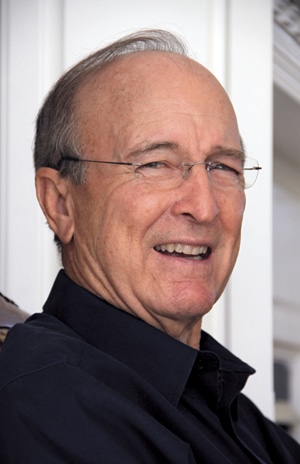

Forty years ago, HPU alumnus Dr. Gary Price was the driving force behind the creation of the Tuition Equalization Grant. Today, he looks back on his long crusade for the passage of this landmark legislation.

By Kyle Mize

If you’ve attended Howard Payne University or any other Texas private college or university since the early 1970s, you may owe Dr. Gary Price a word of thanks.

Four decades ago, this 1960 HPU graduate was the architect of the Tuition Equalization Grant (TEG), which helps offset the difference in tuition rates between private and state institutions in the state of Texas. Since its passage by the Texas Legislature in 1971, three quarters of a million grants have been issued to students in Texas, improving access to private higher education. In 2010 alone, more than $101 million was allocated for students in Texas’ participating institutions, with more than $1.5 million benefiting students at HPU.

Four decades ago, this 1960 HPU graduate was the architect of the Tuition Equalization Grant (TEG), which helps offset the difference in tuition rates between private and state institutions in the state of Texas. Since its passage by the Texas Legislature in 1971, three quarters of a million grants have been issued to students in Texas, improving access to private higher education. In 2010 alone, more than $101 million was allocated for students in Texas’ participating institutions, with more than $1.5 million benefiting students at HPU.

“For many students, the TEG is the determining factor that makes attendance at a private university possible,” says Glenda Huff ’76, HPU’s director of student aid. “I was one of those students. Shortly after the TEG was legislated, I enrolled at HPU and was the recipient of one of the first TEG awards.

“Gary Price formulated the idea of the TEG, wrote the legislation, obtained support for the program and did not rest until it was signed into law,” Huff continues. “He volunteered his time and expertise to make the TEG happen. He opened the door for hundreds of thousands of needy Texas college students to attend private universities. The TEG’s impact on private higher education in Texas is immeasurable.”

Price, whose service to HPU also includes a 21-year tenure on the university’s Board of Trustees, now enjoys his retirement following a distinguished career in law. He recently reminisced about the creation of the TEG, from his initial concept to the bill’s ultimate passage by the Texas Legislature.

Early Days

Aside from four years in Beaumont as a child and stretches of time spent in Houston and Waco for college, Gary Price has lived in Brownwood his entire life – as did generations of Prices before him.

“My parents were born in Brownwood and my grandparents all lived here from the time they were young children,” he says in his relaxed Texas drawl. “I used to be related to about half the county.”

In 1955, this graduate of Brownwood High School began his freshman year at Howard Payne. Price still recalls the excitement and good feeling prevalent on the campus.

“Everybody was optimistic and the school was growing,” he recalls. “Guy Newman was president. He was a very dynamic personality and had a great relationship with students. Everybody admired him and looked up to him.”

Dr. Guy D. Newman, who served as president from 1955 to 1973, remains one of the towering figures in the university’s history. His years at HPU were highlighted by increased enrollment, numerous campus improvements and the creation of HPU’s nationally recognized Douglas MacArthur Academy of Freedom.

For Price, Dr. Newman’s winning personality and ease with people of all walks of life still vividly come to mind.

“He could mix with the wealthiest people and the most powerful, big-time politicians,” Price remembers. “When he drove down the street, he waved at everybody in every car just like he’d known them all his life.”

Though Price ultimately pursued a career in law, he didn’t have that goal in mind when he entered HPU as a freshman. Soon, however, he gained exposure to two fields that would figure prominently not only in his professional life but also in the creation of what would ultimately become the Tuition Equalization Grant: law and politics.

“We had some legal work done within the family, and I saw lawyers in action and always thought it was interesting,” he recalls. “I’d also watch some guys get into politics.”

Though Price later graduated from Howard Payne, during his sophomore year he transferred to the University of Houston to be near his future wife, Jarene Thomas, who lived there with her family. Though UH is now state-supported, at that time it was a private institution, with higher tuition as a result. When registering for classes, Price was presented with an intriguing financial aid opportunity by a UH staff member.

“She asked, ‘Do you want Junior College Aid?’” he remembers. “I asked, ‘What’s Junior College Aid?’ She said, ‘If you’re a Texas resident and you have fewer than 60 credit hours, the state of Texas will pay part of your tuition. All you have to do is sign this card saying that you’re a Texas resident.’

“I said, ‘Gimme the card, I’ll sign that!’”

Price later returned to HPU and after graduation went on to the Baylor University School of Law in Waco. However, the type of financial aid he was offered at UH remained on his mind. He also recalled an important aid program from even earlier.

“Back in elementary school, when World War II ended, I was eight years old,” he says. “I had at least one cousin and knew lots of other people who went to all kinds of trade schools and colleges on the GI Bill. It was a big deal. It’s what educated America after World War II.”

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, which became popularly known as the GI Bill, was enacted during World War II to assist veterans as they returned to civilian life. Though a variety of provisions were included, including those for unemployment pay and loans for homes, farms and businesses, the GI Bill is famous for providing funds for education. In 1947, for instance, 49% of the nation’s college enrollment consisted of veterans, according to the GI Bill website.

“I went to Howard Payne as soon as I got out of high school in ’55, and there were still guys from World War II going to college,” Price recalls. “The Korean War ended when I was a sophomore in high school, and you had a whole generation of those guys going. So I knew a lot of people who were going to school on the GI Bill. It was not an aid to Howard Payne or Baylor – it was an aid to that GI.

“And I thought, ‘Well, my folks and I pay taxes, and we’re helping educate people going to state schools,” he says. “Wouldn’t it be a good idea if there was something to help students attend private schools?”

Getting Started

Throughout his experiences attending Baylor’s School of Law, Price continued to ponder the prospect of the state of Texas making funds available to help students attend private colleges and universities, helping reduce the tuition differences between those and state-supported institutions. He took the law training he was receiving and used it to develop his financial aid concept. For example, though many private colleges and universities are operated by or affiliated with religious denominations, the type of aid Price had in mind would avoid any potential controversies over the separation of church and state. With his plan, the public funding would support the individual student, not the institution – just as the GI Bill had done.

A friend from Price’s Brownwood days also attended law school at Baylor. The late Lynn Nabers, a 1962 HPU graduate, would figure prominently into Price’s plans for the new aid program.

A friend from Price’s Brownwood days also attended law school at Baylor. The late Lynn Nabers, a 1962 HPU graduate, would figure prominently into Price’s plans for the new aid program.

After Price completed his work at Baylor’s School of Law, earning a Doctor of Jurisprudence degree in 1965, he and his wife moved back home to Brownwood, where Price began his law career. Two years later, Nabers earned his J.D. degree and soon decided to run for a state representative position – the seat in the Texas House of Representatives recently vacated by Ben Barnes, who was to become Texas’ lieutenant governor.

Price recalls a chance meeting with Nabers in Austin.

“When he was running for office, I ran into him on the steps of the courthouse,” Price says. “I told him briefly about this idea I had. He said ‘I can’t see the legislature passing something that would help pay the cost of college for all those rich kids in private schools.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve been to three of ’em, and I’ve never seen too many rich kids. And anyway, how about the GI Bill? That was for everybody.’

“And he said, ‘Well, that’s right.’”

After Nabers received his party’s nomination, Price sent a letter to Lieutenant Governor-Elect Ben Barnes with copies to Nabers, Dr. Newman at HPU, key personnel at Baylor and the publisher of the Brownwood Bulletin. The letter informed them of Price’s intentions to find someone in the state’s House of Representatives to sponsor a bill providing grants to students attending Texas’ private colleges and universities.

“Lynn called me and said, ‘I’ll sponsor it if you want me to,’” Price says.

By now, Price had thoroughly developed his proposal. Through his research, he documented how Texas would actually save money. The state would provide grants to Texas residents attending private colleges and universities in amounts of roughly half what it cost the state to educate students at public institutions. By increasing access to private higher education, the plan would save additional state funds through the reduction of costs for instruction and new facilities at state schools as population increased. Texas would also see long-term benefits as a larger number of college graduates would ultimately contribute more to the state’s economy.

After Nabers was elected, the two met to review Price’s draft of what he then called the Tuition Equalization Act. Price recalls the bill’s first steps in the legislative process and one particular first impression.

“I talked to Lynn about the bill and showed him all the reasons for it, arguments for it, and he took it down to the Legislative Budget Board,” Price recalls. “They redrafted the bill and when they were doing it the guy said, ‘You know, this reminds me of Junior College Aid at the University of Houston.’ Lynn told me that and I said, ‘Well, that’s partly where I got the idea for it.’”

Through the course of the next year, Price would periodically call Nabers to check on the bill’s progress – or, more accurately, lack of progress.

“I’d call Lynn and I’d say, ‘Well, what’s happening?’” Price remembers. “He’d say, ‘Well, it’s in the committee. I can’t really find any opposition to it but if you can’t get it out of the committee…’”

Then one day Nabers and Price received an invitation to attend a meeting of Independent Colleges and Universities of Texas (ICUT), to be held on the campus of Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Incorporated in 1965, ICUT works to advance the cause of the state’s private institutions of higher education and represents this network to the state’s lawmakers. The upcoming meeting would be attended by presidents, trustees and other representatives from a variety of private colleges and universities across the state.

When Nabers called Price to ask if he was interested in attending, Price eagerly accepted the opportunity to present his proposal to such an influential audience. He had already compiled a set of packets containing his plan and financial estimates and sent them to each of the presidents of ICUT’s member institutions.

Price and Nabers set off for Dallas, eager to build support for the Tuition Equalization Act. However, they discovered that the long meeting and full agenda would give them little opportunity to make their case.

“We were at this meeting, and they were about to dismiss, and we hadn’t been able to say anything,” Price says. “A president of a Catholic school said, ‘I received this packet in the mail from Mr. Price. I’d like to hear from him about these grants.’ And then a bunch of others spoke up, ‘I got it too, and I’m interested in it. I’d like to hear about it.’”

Price seized the chance to share about his plan. His presentation was well-received, but the meeting’s presiding officer, a college president, offered a dissenting opinion.

“When I sat down,” Price recalls, “he said, ‘I know Mr. Price’s bill sounds good, but I used to work for the Legislative Budget Board of the Texas Legislature and I can assure you: Nothing like that will ever pass.’”

Undeterred, Price and Nabers took their case to Lt. Gov. Barnes. He listened to their proposal, responded favorably and made a couple of phone calls: one to ask a state senator to sponsor the bill in the Senate and another to ask Dr. Bevington Reed, chairman of the state’s College Coordinating Board, to independently verify the proposal’s figures. Barnes set up a meeting for Reed to hear what Price and Nabers had to say.

Price was confident in his research, but was nonetheless apprehensive about the prospect of the bill being sidetracked by another round of official inspection and evaluation. The fact that Dr. Reed presided in Austin, home not only to the state capitol but also to The University of Texas, only added to Price’s fears.

“I’d heard that there’d been a school paper at UT that had been opposed to the TEG,” Price remembers. “The paper said, ‘There shouldn’t be one dime for those students going to private colleges until our requests have been 100% funded. When everything we want has been taken care of, then okay.’

“So I thought, ‘He’s sitting down here in the middle of Austin. Of all the colleges in the state of Texas, he’s going to be a UT guy – he’s not going to care about private schools.’”

Price and Nabers were in for a surprise.

“When we walked in there,” Price recalls, “Dr. Reed stuck out his hand and said, ‘How’s my old friend Guy Newman? He’s always trying to get me to come to Brownwood. I’ve only been there one time since I graduated from Daniel Baker College.’

“And I thought, ‘THANK YOU, LORD!’”

Price was stunned. Not only was Dr. Reed not a UT graduate, but he was a graduate of Daniel Baker College, the Presbyterian institution in Brownwood that had merged with Howard Payne in 1953. And best of all, he was a friend of Dr. Guy D. Newman, HPU’s president.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Price says, laughing. “He was so nice and friendly. He said, ‘Tell me about it.’ At the end, he said, ‘I can tell you, I’ve heard every kind of proposal you can think of, and that’s the most practical, the best one I’ve ever heard of. We’ll go to work on it.’”

After the meeting with Dr. Reed, Price and Nabers went to see the state senator who had been contacted by Lt. Gov. Barnes.

“He said, ‘I’ll introduce it because Ben asked me to, but it ain’t gonna pass,’” Price remembers.

Time would tell.

Moment of Truth

The final report on the proposed Tuition Equalization Act was forwarded to Lynn Nabers in early 1969. The bill didn’t make it through the committee process in time for the legislature’s session that year. The next year also passed without a decision. Price still remembers how he felt when the bill was reintroduced in 1971.

“I was scared to death,” he says. “Lynn called me and said, ‘Come down to Austin. I think they’re going to vote on it in the House today.’ So I went down there and sat up in the gallery.”

As private universities had gotten more involved in supporting the bill, it had been revised so that grants would be awarded based on need.

“When I introduced it, it was for all students,” Price says. “Like the GI Bill was aid to GIs because they were GIs, this is aid to Texas residents because they’re Texas residents, and they’re taxpayers. But two years later when it got introduced, it was limited to people who had financial need. They said, ‘It can’t ever pass otherwise.’”

That day in Austin, Price watched one of the representatives propose another amendment, this time to prevent students who receive athletic scholarships from receiving TEG funding. This amendment also passed.

“Then there were other things going on down there,” Price recalls, “so Lynn went over and grabbed that microphone. He did a super job. An absolutely super job. That ended it, they voted, it passed by a landslide and then passed a week or two later in the Senate by a landslide. That was it.”

Even with the two changes, limiting funds to students with financial need and who receive no athletic scholarships, the Tuition Equalization Grant has gone on to make an incalculable impact by improving access to private higher education in Texas. In each year since the bill became law, the Texas Legislature has appropriated funds for the TEG program. This funding has then been distributed by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, providing direct assistance to selected students who meet the TEG program’s criteria.

While other states now have similar programs, to the best of Price’s knowledge Texas was the first. Thinking back over the sequence of events that took the TEG from his earliest concept to its final passage, Price is grateful for the experiences that helped make it possible.

“I’m glad that all those events happened, because if those circumstances hadn’t existed, I would never have just dreamed it up out of the clear blue,” he says. “Somebody might have, but I wouldn’t have. If I hadn’t gone to Howard Payne, if I hadn’t lived in Brownwood, if I hadn’t been at the age to hear about people going on the GI Bill after World War II and Korea, if I hadn’t gone to the University of Houston, if I hadn’t gone to law school at Baylor, it would have never happened.”

In the decades since the TEG’s creation, Price maintained a private practice and served variously as county attorney and district attorney while participating in a wide range of civic organizations in Brownwood. On the 20th and 30th anniversaries of the TEG bill’s passage, he was presented proclamations by the Texas Legislature in continuing recognition of his landmark achievement. In December 2010, in appreciation of his work on the TEG and other accomplishments, HPU awarded him the honorary Doctor of Humanities degree, the highest honor the university can bestow.

Through the years, Price has been surprised by occasional expressions of appreciation for his role in the TEG’s creation so many years ago.

“We were taking depositions over at the office one day, and took a recess for a minute,” he recalls. “A young lawyer came back in and said, ‘I owe you a debt of gratitude.’ Well, I was thinking about depositions for the lawsuit, so I asked, ‘About what?’

“He said, ‘I see you were responsible for the TEG, and I went to college and law school both on that.’

“And the other guy sitting there looked up and said, ‘Me too.’”

Now enjoying an active retirement, he still considers the process of creating the TEG one of the most gratifying experiences of his life.

“It was fun, it was interesting to do it and I met a lot of interesting people,” he summarizes, pensively. “And obviously, just knowing that that many people have gotten grants … There had to be many thousands of them who would never have gone to college otherwise. And college changes anybody’s life.”

###